Hannah Gadsby reminds us that anger is a forbidden feeling. Forbidden to whom? To women, obviously. Female anger, dear sisters, is instantly recognised as an extreme state, rather than one of emotional commonplaces. It’s unbecoming to women. And that’s why I’d like to begin by posing a question: can one feel feelings? Do women who are looking feel anger, awe, or perhaps attraction?

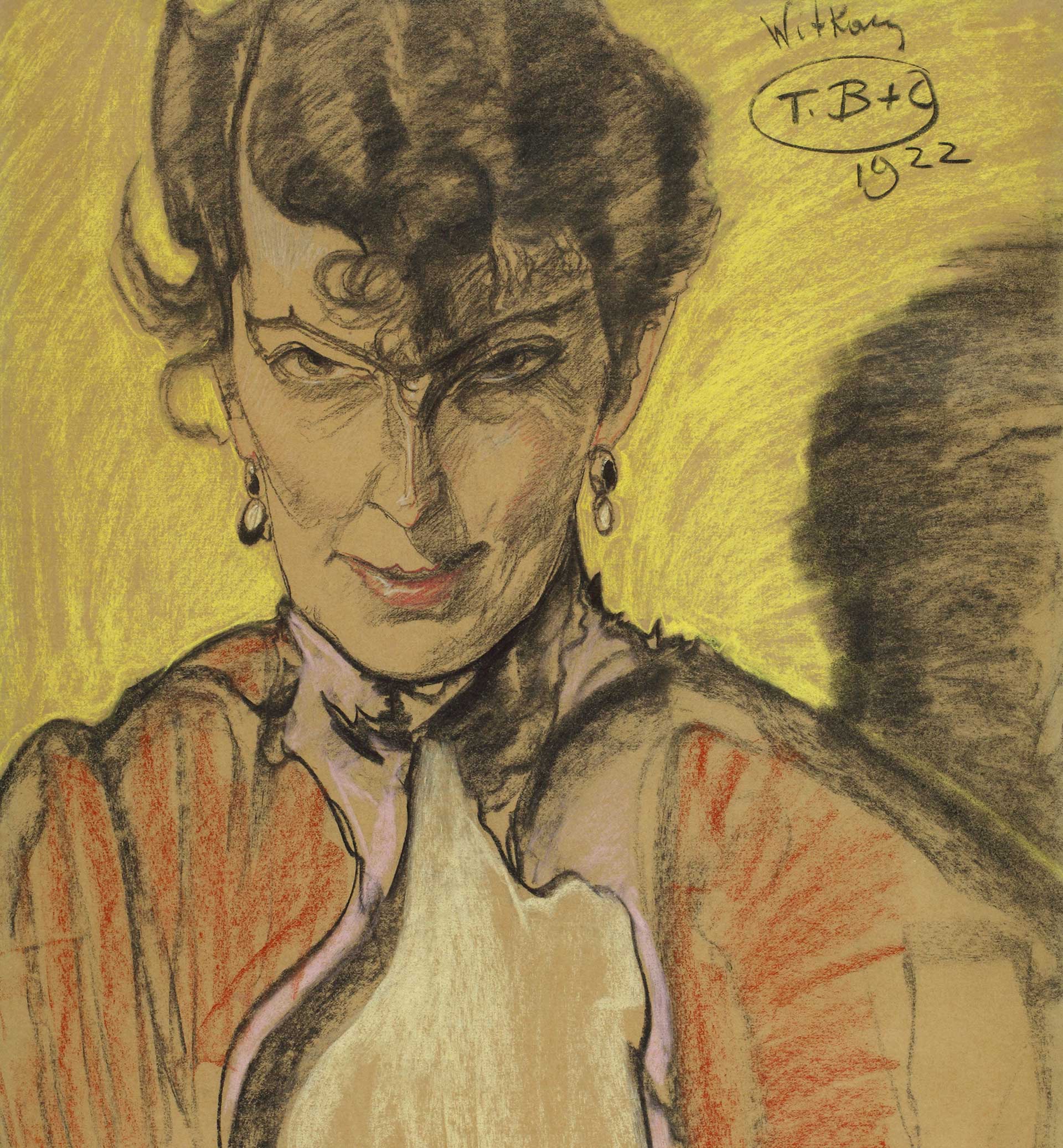

With black pencil strokes, Witkacy demarcates the red of the woman’s coat from the symbolic bile-like yellow. He applies pastel upon pastel, layering the unconscious onto the conscious. But the male stroke doesn’t appropriate everything. Had Witkacy exerted more pressure on the coloured pencil, he could have filled in the gaps, the deficiencies, the breaks, the silence, and the understatement. Fortunately, the artist shied away from narrative excessiveness and didn’t mansplain female anger. The portrait oozes corporeality, with the page the colour of flesh or egg yolk. In a true intertextual fashion, the poet Tadeusz Różewicz comes to Witkacy’s aid in “The Story of Old Women” (trans. Joanna Trzeciak): “Because (…) old women / are like an ovum / a mystery devoid of mystery / a sphere that rolls in”.

Let’s also consider the abbreviation up in the top right-hand corner. It was the artist’s wont. “T.B.” stands for a more pronounced portrait: more emphasis on character, yet without any trace of caricature. Above that, Witkacy added “C” for C2H5OH, or ethyl alcohol, under the influence of which the artist was painting. He could have followed a different path. Many of Witkacy’s portraits of women are emblazoned with “T.A.”, the byword for his relatively more streamlined, slick, and mainstream painting. “Suitable more to female rather than to male faces”, as he explained. Yet this isn’t so. Here, the anger on the demonic woman’s face is far from smooth and superficial.

Let me then repeat once again: one single frame of female anger does suffice!